CIENCIAS AGROPECUARIAS-Artículo Científico

ANALYSIS OF PURPLE PASSION FRUIT (Passiflora edulis Sims) GROWTH UNDER ECOLOGICAL CONDITIONS OF THE COLOMBIAN LOWER MONTANE RAIN FOREST

ANÁLISIS DE CRECIMIENTO DEL FRUTO DE GULUPA (Passiflora edulis Sims), EN LAS CONDICIONES ECOLÓGICAS DEL BOSQUE HÚMEDO MONTANO BAJO DE COLOMBIA

Germán Franco1, José R. Cartagena2, Guillermo Correa3

1Dr. Sc. Researcher. C. I. La Selva, Corpoica. Rionegro, Antioquia, Colombia.gfranco@corpoica.org.co

2Ph.D. Department of Agronomic Sciences, Full Professor, Universidad Nacional de Colombia-Sede Medellín, Colombia; jrcartag@unal.edu.co

3Dr. Sc. Department of Agronomic Sciences, Associate Professor, Universidad Nacional de Colombia-Sede Medellín, Colombia; gcorrea@unal.edu.co

Rev. U.D.C.A Act. & Div. Cient. 17(2): 391-400, Julio-Diciembre, 2014

SUMMARY

High-Andean fruits are considered important for their domestic consumption and exportation potential. Among them, purple passion fruit (Passiflora edulis Sims) is largely accepted in European markets. However, its short shelf life, worsened with the limited knowledge of the species lead to rapid fruit deterioration. An important contribution to the development of this crop is fruit growth mathematical modeling, which allows estimating harvest related issues, in order to define applicable agronomic management protocols. Periodic destructive sampling was employed to investigate fruits of known age corresponding to ten purple passion fruit materials from the Colombian departments of Antioquia, Putumayo and Nariño. The fruits were analyzed for dry weight, polar and equatorial diameters, thermal time (TT) and relative growth rate (RGR). In order to assess fruit growth, some nonlinear models were fitted using time after flowering (DAF) to predict dry weight and polar and equatorial diameters. For each response, the best fitting model was chosen according to homogeneous distribution of residuals, higher coefficient of determination for prediction (R2 prediction), and smaller Mean Square Error and PRESS values. RGR was used to identify and describe fruit growth stages, while the TT was employed as a complementary measure to compare fruit ripening stages. The studied parameters were satisfactorily explained by Weber's Monomolecular model. Based on the models adjusted for fruit growth, it can be concluded that harvest must be carried out between days 85 - 90 after full bloom.

Key words: Growth dynamics, fruit development, tropical fruits, Passifloraceae.

RESUMEN

Los ''frutales alto-andinos'' se consideran importantes por su potencial de consumo nacional y exportación. La gulupa (Passiflora edulis Sims) es un frutal de buena aceptación en mercados europeos; sin embargo, el poco conocimiento de la especie y corta vida poscosecha, conducen al rápido deterioro del fruto. Una contribución importante para el desarrollo del cultivo, es la modelación matemática del crecimiento del fruto, que permita estimar aspectos relacionados con la cosecha, con el propósito de definir protocolos aplicables en su manejo agronómico. Se realizaron muestreos destructivos periódicos de frutos con edad conocida, pertenecientes a diez materiales de gulupa procedentes de los departamentos de Antioquia, Putumayo y Nariño (Colombia). A los frutos se les determinó el peso seco, los diámetros polar y ecuatorial, el tiempo térmico (TT) y la tasa de crecimiento relativo (TCR). Para analizar el crecimiento del fruto, se emplearon modelos no lineales, en los que los días después de floración (DDF) se utilizaron para predecir el peso seco y los diámetros polar y ecuatorial. Para cada respuesta, se eligió el modelo con mejor ajuste según presentara una distribución más homogénea de los residuales, mayor coeficiente de determinación para predicción (R2predicción), menor Error Cuadrático Medio y menor valor del estadístico PRESS. La TCR sirvió para delimitar y describir las fases del crecimiento del fruto en tanto que el TT se empleó como medida complementaria para comparar con los estados de maduración del fruto. Se encontró que las variables en estudio fueron explicadas satisfactoriamente por el modelo Monomolecular-Weber. Con base en los modelos ajustados, se puede inferir que la cosecha debe realizarse entre los 85 y 90 días siguientes a la plena floración.

Palabras clave: Dinámica del crecimiento, desarrollo del fruto, frutas tropicales, pasifloras.

INTRODUCTION

Usually marketed fresh, high-Andean fruits are highly demanded by consumers. Their short shelf life determines rapid deterioration of physiological functions, which affects fruit quality and makes it necessary to conduct characterization studies on the physical, physiological and biochemical processes that accompany the ripening process (Andrade- Cuvi et al. 2013; Ramírez et al. 2013; Torres et al. 2013). A wide range of fruit species with potential to be developed as commercial crops has been recognized in the Colombian Andes (Schotsmans & Fischer, 2011; Lagos-Santander et al. 2013; Llanos et al. 2013; Abreu et al. 2014). Among them, purple passion fruit (Passiflora edulis Sims) exists, most of which production is currently exported, amounting 3,319 t in 2012, traded for an FOB value of U.S. $ 15,766.034, mostly to European markets (CCB, 2014).

Following Aristizábal (2003), studies about fruit growth (mainly dealing with irreversible size and dry weight increase) and development (gradual change in size, structure and function) are important to assess optimum ripening stage (Cañizares et al. 2003; Tapia et al. 1998), determine growth behavior through time, estimate fruit size (Avanza et al. 2008) and weight (Coombe, 1976) at harvest, propose agricultural management strategies (Rojas et al. 2008; Casierra & Cardozo, 2009), establish phenological stages, and analyze fruit formation and structural development (Mazorra et al. 2006).

A mathematical model allows synthesizing and increasing knowledge about a given system (López et al. 2005), evaluating potential management strategies and estimating potential yield, costs and benefits obtained with the use of specific practices such as fertilization, irrigation, or even commercial transactions (Cañizares et al. 2003; Tapia et al. 1993). Among the non-linear models used to characterize growth and/or development as functions of time, the logistic, monomolecular, exponential (Aristizábal, 2003; Rojas et al. 2008) and Michaelis-Menten (Rojas et al. 2008) models hold an outstanding place.

Characterized by its sigmoid shape, the logistic model results from the combination of the exponential and monomolecular models, separated by an inflection point. The exponential model describes steady growth progress (decline) (Rojas et al. 2008) as the result of previously accumulated (lost) weight; thus explaining why small seeds produce smaller seedlings than those produced by medium or large seeds (Aristizábal, 2003).

The monomolecular model shows how a plant's dry weight change rate is determined by future growth, thus estimating growth rates steady decline as the fruit reaches full size (Aristizábal, 2003). It has been used to estimate the growth of different plant and pathogen structures, as is the case of sweet orange (Citrus sinensis var. Valencia Late) fruit growth, modeled by Avanza et al. (2008). These authors resorted to diameter as a function of days after full flowering, as represented by the equation Diameter (mm) =G(1-βe(-Y*DDPF)) Rojas et al. (2008) estimated fresh weight of Manzano hot pepper (Capsicum pubescens) through the function Y = a(1- eb), by measuring non-destructive parameters such as water volume displaced by the fruit in a graduated cylinder. Costa et al. (2002) have observed that Mitscherlich's monomolecular model can be applied to the simulation of disease progress, prevention and resulting damage and losses. In this case, disease progress rate is proportional to initial inoculum amount and progress rate, both assumed to be constant. The equation that describes the model is dx/dt=rM(1-x) being the specific rate for this model (rM = initial inoculum*rate), and (1-x) representing the healthy tissue. Michaelis-Menten's model is recommended to describe plant growth in response to limiting factor increases (Mancera et al. 2003).

Replacing the Gaussian function coefficients with mathematical functions that include the effect of population density, Villegas et al. (2004) obtained kinetic models that simulate total biomass growth in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) cv. Gabriela, under greenhouse conditions and defined agronomic management. Tapia et al. (1993) adjusted equations proposed by Bailey & Clutter (1974) to explain the development of equatorial diameter and age in olives (Olea europaea). In the same vein, Cañizares et al. (2003) described the growth of the fruit of guava (Psidium guajava) with a double sigmoid curve. In turn, Casierra & Cardozo (2009) adjusted cubic models to fruits of tomato cv. Quindío, grown in open field conditions. Finally, Rojas et al. (2008) recommend the monomolecular model to estimate fruit dry weight increase in Manzano hot pepper by means of a single non-destructive parameter: water volume displaced by the fruit in a graduated cylinder.

Shiomi et al. (1996) and Carvajal et al. (2012) observed a rapid length and diameter increase in fruits of purple passion fruit around the 20th day after flowering (DAF), and considered it as a species-specific pattern. Fruit weight in this crop was observed to increase until 20 DAF (Shiomi et al. 1996), whereas Carvajal et al. (2012) found this rise to continue until 42 DAF, followed by a more gradual progress towards the ripening period. Shiomi et al. (1996) also reported a second weight rise, probably due to juice accumulation. While some fruits such as peach (Prunus persica) (Salisbury & Ross, 1994) exhibit double sigmoid growth, others have simple sigmoid growth, as is the case of passion fruit (Passiflora edulis) (Lederman & Gazit, 1993), champa (Campomanesia lineatifolia) (Álvarez et al. 2009) and star fruit (Averrhoa carambola) (González et al. 2001). Thus, based on nonlinear models, the objective of this study was to model purple passion fruit growth to serve as a reference in planning of cultural practices associated with the harvest.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The evaluated crop was grown in the municipality of Rionegro, rural settlement of Llanogrande, department of Antioquia, at La Selva Research Center of Corporación Colombiana de Investigación Agropecuaria - Corpoica (6o 7' 49'' N, 75o 24' 49'' W; 2,090 m.a.s.l.). Climatic parameter yearly average scores were: temperature, 17°C; precipitation, 1,917 mm; relative humidity (RH), 78%; sunshine, 1,726 hours year- 1, evapotranspiration, 1,202 mm. The climate corresponds to a Lower Montane Rain Forest. The trial was conducted in an experimental area where 10 purple passion fruit accessions were randomly planted. The materials are part of the Colombian Gene Bank (administered by Corpoica), which after Amplified Length Polymorphism (AFLP) and Simple Sequence Repeat (SSR) molecular analysis, was reported to have low genetic variability (Ortiz et al. 2012). Fruit tracking was done by labeling flowers with and without herkogamy at their homogamous phase, making use of colored threads (Ángel et al. 2011). Fruit age was measured in days after flowering (DAF), corresponding the day of flower labeling to day zero (0 DAF).

Destructive samplings were carried out every seven days for a period of 16 weeks, starting on 7 DAF, and finishing on

112 DAF. Each sampling consisted in ten randomly chosen fruits. The samples were transported in expanded polystyrene boxes containing dry ice to keep an internal temperature of 4°C. Fruit parameters determination was carried out at the post-harvest laboratory of Corpoica, under average temperature and relative humidity (RH) conditions of 20°C and 70%, respectively.The following variables were recorded:

Dry weight (DW). Expressed in grams. This parameter was obtained after oven dry fruits at 70°C. until they reached constant weight.

Polar (PD) and equatorial (ED) diameters. These parameters were measured in centimeters on each fruit, with a digital L&W Tools™ caliper. Polar diameter was taken from the peduncle insertion scar to the opposite extreme of the fruit. Equatorial diameter was taken along the widest belt of the fruit.Thermal Time (TT). This concept is based on the notion that in order to shift from one growing stage to another, plants need to accumulate minimum amounts of temperature. In consonance with Fischer et al. (2009), the base temperature (Tb) has been fixed at 10°C. Conceptually, base temperature is the temperature at which development stops through cold. In the current study, TT (expressed as Growing Degree Days - GDDs) was calculated according to the simple triangle methodology proposed by the University of California (2013).

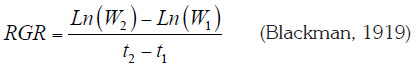

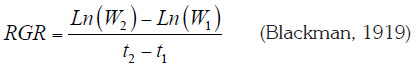

Relative Growth Rate (RGR). This parameter addresses dry weight increment per initial weight unit along a given time period. It was deduced through the following equation:

Ln = Natural logarithm; W1 = Initial weight; W2 = Final weight; t1 = Starting time; t2 = Final time

Fruit growth analysis was preceded by the evaluation of the non-linear models reported by Kiviste et al. (2002). Each model was adjusted for dry weight, polar diameter and equatorial diameter, always using DAF as the predictive variable. For each response variable, we chose the best fitting model, i.e., the one offering the most homogeneous residual distribution, the highest predicted coefficient of determination (R2prediction), and the lowest values of the PRESS statistic and Mean Square Error. RGR was used to limit and describe the different fruit growth stages, whereas TT was employed as a complementary measure to compare fruit ripening stages.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

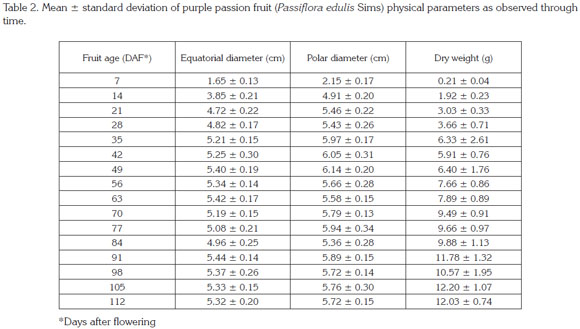

Dry weight. Purple passion fruit increased during all the growing stage. Growth is mainly due to cell division until it reaches an ED of 4.72cm and a PD of 5.46 cm. From then on, size increment is the result of cell elongation taking place mainly at the mesocarp (González et al. 2001).

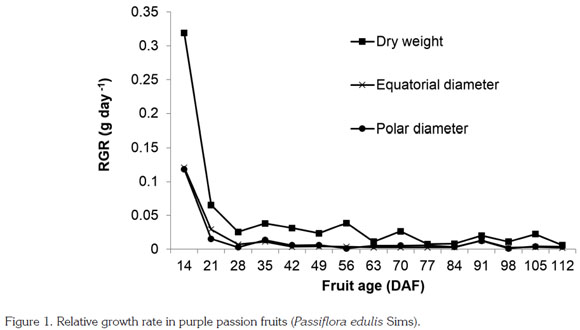

Three growing periods were identified: an initial stage went until 14 DAF, with a RGR of 0.319 g day-1; the second stage took up to 28 DAF, with a RGR of 0.065 g day-1; and the final stage took up to 112 DAF, RGR being 0.0255 g day-1 (Figure 1). This indicates that growth takes place mainly during the first month. RGR approached zero at about 91 DAF. Hence, under the conditions of the current study, fruit harvest can be carried out at 85 - 90 DAF, when accumulated TT was 589.73 and 635.23 GDDs.

In studying purple passion fruits, Shiomi et al. (1996) observed a rapid fresh weight increase that lasted until 20 DAF and went on at a slow pace until ripening. Flórez et al. (2012) report an 85 - 90 DAF period before reaching physiological maturity, corroborated through seed characteristics, which, in contrast to previous stages, corresponded to a hard, black seed coat. That work also reports inter-cellular space enlargement inside the fruit during the first 20 to 35 DAF. Carvajal et al. (2012) observed physiological maturity at around 80 DAF, whereas Pinzón et al. (2007) recommend stage three of the fruit color scale they developed as the optimum harvest moment, but they do not mention any approximate fruit age.

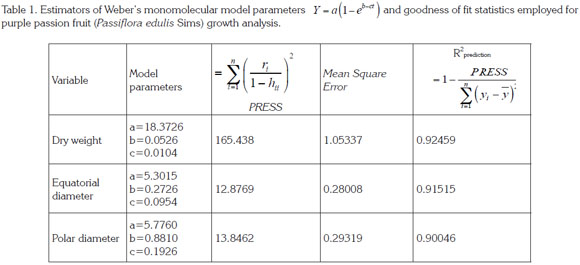

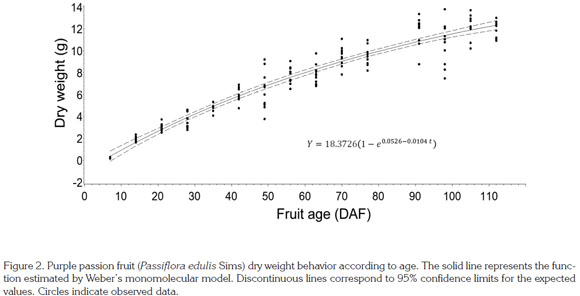

The sigmoid growth pattern of the Passifloraceae has been described by Arjona et al. (1991), Lederman & Gazit (1993), Pocasangre et al. (1995), Gómez et al. (1999), Villanueva et al. (1999) and García (2008). In accordance with the results of the current study, Shiomi et al. (1996) found the same tendency in purple passion fruit. Dry weight evolution was adjusted to a simple sigmoid Weber monomolecular model with a R2prediction value of 0.92 (Table 1; Figure 2).

Other authors have described this same parameter through different models. Almanza et al. (2009) adjusted a logistic model to grape (Vitis vinifera) growth; González et al. (2001) adapted a polynomial model in star fruit; Casierra & Cardozo (2009) fitted a cubic model in tomato cv. Quindío; Hernández & Martínez (1994) developed a quadratic model for tree tomato; and Rodríguez et al. (2006) generated a cubic model for pineapple guava (Acca sellowiana). All these models exhibited large R2 values, thus showing their remarkable predictive capacity.

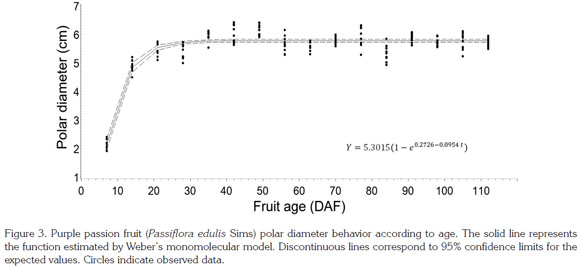

Polar diameter. This parameter was fitted by a simple sigmoid W Weber monomolecular model with a R2prediction value of 0.90 (Table 1; Figure 3). Swift growth lasted until 21 DAF, when it tended to stabilize, as also observed by Shiomi et al. (1996), Carvajal et al. (2012) and Flórez et al. (2012) in this same fruit; in passion fruit by Arjona et al. (1991), Lederman and Gazit (1993), Tapia et al. (1998) and Gómez et al. (1999); and in sweet grenadilla (Passiflora ligularis by García (2008). Around this time, the fruit reaches definite size, followed by cell differentiation and fruit filling, as reported by Salisbury & Ross (1994) in describing the timing of this process. The values obtained for this parameter in the current study are within the range described by Orjuela et al. (2011) (Table 2). As it is observable in this fruit's characteristic shape, simple polar diameter was found to be larger than equatorial diameter, in agreement with reports by Gómez et al. (1999) in purple passion fruit and by García (2008) in sweet grenadilla.

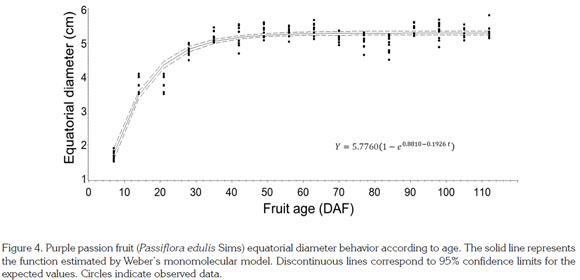

Equatorial diameter. This parameter showed sigmoid behavior, in agreement with previous observations by Shiomi et al. (1996) in purple passion fruit, by Arjona et al. (1991) in mayop (P. incarnate) and purple passion fruit, and by Villanueva et al. (1999) and Gómez et al. (1999) in yellow passion fruit. In the mentioned species, the exponential phase occurs between seven and 15 days after anthesis, depending on the environment where the fruits have grown. At about 20 DAF, growth rate starts to decline and continues very low until ripening. After modeling equatorial diameter with Weber's monomolecular model, García (2008) found a similar behavior in sweet grenadilla, which showed a R2 value of 0.91 (Table 1; Figure 4), thus exhibiting a sigmoid growth pattern similar to that of the polar diameter and to scores reported by Orjuela et al. (2011).

In this regard, Carvajal et al. (2012) observed that purple passion fruit diameter and length underwent a rapid growth stage until the fifth week of age and then stabilized until the tenth week; which is not entirely consistent with the findings of this study. Likewise, Pinzón et al. (2007) found that this plant produces fruits with respective polar and equatorial diameters of 50 and 56 mm, which decline along the ripening process, thus setting a contrast with the present study, in which the polar (longitudinal) diameter always showed higher values than the equatorial diameter (57 and 53mm respectively). This situation could probably be due to differences in the studied genetic materials.

To summarize: the description of the fruit growth is a useful element for the future construction of a model, that achieves simulate the potential production of purple passion fruit crop. Analysis of purple passion fruit growth and development serves as a guide for scheduling crop management practices such as pruning, fertilization and irrigation, in order to optimize the source/sink relations. Nonetheless, as the plant is constantly bearing fruit at different developmental stages, the average demand is relatively constant, which is why agricultural tasks should be based on the predominant fruit developmental stage. Based on the model adjusted to fruit growth, it is possible to foresee that harvest can be scheduled on days 85 - 90 after an abundant flowering, since the equatorial and polar diameters and dry weight tended to stabilize. The values estimated by the model explain each of the variables determined in relation to field observations, therefore, properly interpret the physiological processes taking place in the fruit in each of their ages.

Conflicts of interest: The manuscript was prepared and reviewed with the participation of all the authors, who declare that no conflict of interest that threatens the validity of the results presented.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. ABREU, O.A.; BARRETO, G.; PRIETO, S. 2014. Vaccinium (Ericaceae): Etnobotany and pharmacological potentials. Emir J. Food Agric. 26(7):577-591.

2. ALMANZA, P.J.; BALAGUERA, H.E. 2009. Determinación de los estadios fenológicos del fruto de Vitis vinifera L. bajo condiciones del altiplano tropical en Boyacá. Rev. U.D.C.A Act. & Div. Cient. (Colombia). 12(1):141-150.

3. ÁLVAREZ, J.G.; GALVIS, J.A.; BALAGUERA, H.E. 2009. Determinación de los cambios físicos y químicos durante la maduración de frutos de champa (Campomanesia lineatifolia R. & P.). Agron. Colomb. (Colombia). 27(2):253-259.

4. ANDRADE-CUVI, M.J.; MORENO-GUERRERO, C.; CONCELLÓN, A.; CHICAIZA-VÉLEZ, B. 2013. Efecto hormético de la radiación UV-C sobre el desarrollo de Rhizopus y Phytophthora en naranjilla (Solanum quitoense). Rev. Iber. Tecnología Postcosecha. 14(1):64-70.

5. ÁNGEL, C.; NATES, G.; OSPINA, R.; MELO, C.D.; AMAYA, M. 2011. Biología floral y reproductiva de la gulupa Passiflora edulis Sims f. edulis. Caldasia (Colombia). 33(2):43-451.6. ARISTIZÁBAL L., M. 2003. Fisiología Vegetal. Universidad de Caldas (Manizales). 306p.

7. ARJONA, H.E.; MATTA, F.B.; GARNER, J.A. 1991. Growth and composition of passion fruit (Passiflora edulis) and mayop (P. incarnata). HortScience (USA). 26(7):921-923.

8. AVANZA, M.M.; BRAMARDI, S.J.; MAZZA, M. 2008. Statistical models to describe the fruit growth pattern in sweet orange ʹValencia lateʹ. Span. J. Agric. Res. (Spain). 6(4):577-585.

9. BAILEY, R.L.; CLUTTER, J.R. 1974. Base-age in variant polymorphic site curves. Forest Science (USA). 20:155-159.

10. BLACKMAN, V.H. 1919. The compound interested law and plant growth. Ann. Bot. (UK). 33(3):353-360.

11. CÁMARA DE COMERCIO DE BOGOTÁ. 2014. Especial de gulupa, tomate de árbol y lulo. Retrived from: ccb.org.co/contenido/contenido.aspx?catID=944& conID=14464; (accessed on: 17/08/2014).

>12. CAÑIZARES, A.; LAVERDE, D.; PUESME, R. 2003. Crecimiento y desarrollo del fruto de guayaba (Psidium guajava L.) en Santa Bárbara, Estado de Monagas, Venezuela. Rev. Cient. UDO Agrícola (Venezuela). 3(1):38-38.

13. CARVAJAL, V.; ARISTIZABAL, M.; VALLEJO, A. 2012. Caracterización del crecimiento del fruto de la gulupa (Passiflora edulis f. edulis Sims). Agron. (Colombia). 20(1):77-88.

14. CASIERRA, F.; CARDOZO, M.C. 2009. Análisis básico del crecimiento en frutos de tomate (Lycopersicon esculentum cv. Quindío) cultivados a campo abierto. Rev. Fac. Nal. Agr. Medellín (Colombia). 62(1):4815- 4822.

15. COOMBE, B.G. 1976. The development of fleshy fruits. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiology (USA). 27:207-228.

16. COSTA, L.C.; JUNIOR, W.C.; RIBEIRO DO VALE, F.X. 2002. Modelos aplicados en fitopatología. Rev. FCA UN Cuyo (Argentina).34:81-92.

17. FISCHER G.; CASIERRA-POSADA, F.; PIEDRAHÍTA, W. 2009. Ecofisiología de las especies pasifloras cultivadas en Colombia. In: MIRANDA, G.; FISCHER, G.; MAGNITSKYI, S.; CASIERRA-POSADA, F.; PIEDRAHÍTA, W.; FLÓREZ, L.E. eds. Cultivo, poscosecha y comercialización de las pasifloráceas en Colombia: maracuyá, granadilla, gulupa y curuba. Sociedad Colombiana de Ciencias Hortícolas (Bogotá). p.45-67.

18. FLÓREZ, L.M.; PÉREZ, L.V.; MELGAREJO, L.M.; HERNÁNDEZ, S. 2012. Manual calendario fenológico y fisiología del crecimiento y desarrollo del fruto de gulupa (Passiflora edulis Sims) de tres localidades del departamento de Cundinamarca. In: Melgarejo, L.M. Ecofisiología del cultivo de la gulupa (Passiflora edulis Sims). Produmedios (Bogotá). p.33-51.

19. GARCÍA, M.C. 2008. Manual de manejo cosecha y poscosecha de granadilla. Produmedios (Bogotá). 100p.

20. GÓMEZ, K.; ÁVILA, E.; ESCALONA, A. 1999. Curva de crecimiento, composición interna y efecto de dos temperaturas de almacenamiento sobre la pérdida de peso de frutos de parchita 'Maracuya' (Passiflora edulis f. flavicarpa Degener). Rev. Fac. Agron. (LUZ) (Venezuela). 25:125-137.

21. GONZÁLEZ, D.V.; HERNÁNDEZ, M.S.; HERRERA, A.; BARRERA, J.A.; MARTÍNEZ, O.; PÁEZ, D. 2001. Desarrollo del fruto e índices de cosecha de la carambola (Averrhoa carambola L.) producida en el piedemonte amazónico colombiano. Agron. Colomb. (Colombia). 18(1-2):7-13.

22. HERNÁNDEZ, M.S.; MARTÍNEZ, O. 1994. Cambios morfológicos del fruto de tomate de árbol (Cyphomandra betacea. var. Tamarillo). Rev. Comalfi (Colombia). 21(1):7-13.

23. KIVISTE, A.; ÁLVAREZ, J.G.; ROJO, A.; RUIZ, A.D. 2002. Funciones de crecimiento de aplicación en el ámbito forestal. Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnología. Instituto Nacional de Investigación y Tecnología Agraria y Alimentaria INIA. Forestal 4 (Madrid). p.190.

24. LAGOS-SANTANDER, L.K.; VALLEJO, F.A.; LAGOS, T.CC.; DUARTE, D.E. 2013. Correlaciones genotípicas, fenotípicas y ambientales, y análisis de sendero en tomate de árbol (Cyphomandra betacea Cav. Sendt). Acta Agron. 62(3):215-222.

25. LLANOS, W.J.; CASTILLO, B.; LONDOÑO, M.T. 2013. Caracterización de propiedades mecánicas del fruto de la uchuva (Physalis peruviana L.). Agron. Colomb. (Colombia). 31(1):76-82.

26. LEDERMAN, E.; GAZIT, S. 1993. Growth, development and maturation of the purple (Passiflora edulis Sims.) the whole fruit. Pesq. Agropec. Bras. (Brasil). 28(10):1195-1199.

27. LÓPEZ, I.L.; RAMÍREZ, A.; ROJANO, A. 2005. Modelos matemáticos de hortalizas en invernadero: Trascendiendo la contemplación de la dinámica de cultivos. Rev. Chapingo serie Horticultura (México). 11(2):257- 267.

28. MANCERA, J.E.; PEÑA, E.J.; GIRALDO H, R.; SANTOS, A. 2003. Introducción a la modelación ecológica. Principios y aplicaciones. Universidad Nacional de Colombia Universidad del Magdalena (Santafé de Bogotá). 112p.

29. MAZORRA, M.F.; QUINTANA, A.P.; MIRANDA, D.; FISCHER, G.; CHAPARRO DE V, M. 2006. Aspectos anatómicos de la formación y crecimiento del fruto de uchuva Physalis peruviana (Solanaceae). Acta Biol. Colomb. (Colombia). 11(1):69-81.

30. ORJUELA, N.M.; CAMPOS, S.; SÁNCHEZ, J.; MELGAREJO, L.M.; HERNÁNDEZ, M.S. 2011. Manual de manejo poscosecha de gulupa (Passiflora edulis Sims). In: Melgarejo, L.M.; Hernández, M.S. Poscosecha de la Gulupa (Passiflora edulis Sims). Universidad Nacional de Colombia (Bogotá). p.7-22.

31. ORTIZ, D.C.; BOHÓRQUEZ, A.; DUQUE, M.C.; THOME, J.M.; CUELLAR, D. ; MOSQUERA, T. 2012. Evaluating purple passion fruit (Passiflora edulis Sims f. edulis) genetic variability in individuals from comercial plantations in Colombia. Genet. Resour. Crop Ev. (Netherlands). 59 (6):1089-1099.

32. PINZÓN, I.M.; FISCHER, G.; CORREDOR, G. 2007. Determinación de los estados de madurez del fruto de la gulupa (Passiflora edulis Sims). Agron. Colomb. (Colombia). 25 (1):83-95.

33. POCASANGRE, H.E.; FINGER, F.L.; BARROS, R.S.; PUSCHMANN, R. 1995. Development and ripening of yellow passion fruit. J. Hort. Sci (USA). 70 (4):573-576.

34. RAMÍREZ, J.D.; ARISTIZABAL, I.D.; RESTREPO, J.I. 2013. Coservación de la mora de castilla mediante la aplicación de un recubrimiento comestible de gel de mucílago de penca de sábila. Vitae 20(3):172-183.

35. RODRÍGUEZ, M.; ARJONA, H.E.; CAMPOS, H.A. 2006. Caracterización fisicoquímica del crecimiento y desarrollo de los frutos de feijoa (Acca sellowiana Berg) en los clones 41 (Quimba) y 8-4. Agron. Colomb. (Colombia). 24(1):54-61.

36. ROJAS, P.C.; PÉREZ, M.; COLINAS, M.T.; SAHAGÚN, J.; AVITIA, E. 2008. Modelos matemáticos para estimar el crecimiento de chile manzano. Revista Chapingo serie Horticultura (México). 14(3):289-294.

37. SALISBURY, F.B.; ROSS, C.W. 1994. Fisiología Vegetal. Grupo Editorial Iberoamericana S. A. (México, D.F.) 759 p.

38. SHIOMI, S.; WAMOCHO, L.S.; AGONG, S.G. 1996. Ripening characteristics of purple passion fruit on and off the vine. Postharvest Biol. Tech. (USA). 7(1-2):161-170.

39. SCHOTSMANS, W.C.; FISCHER, G. 2011. Passion fruit (Passiflora edulis Sims. In: Yahia, E. (ed). Postharvest biology and technology of tropical and subtropical fruits. Mangosteen to white sapote. Vol.4. Woodhead Publ. Cambridge, U.K. p.125-142.

40. TAPIA, L.; BASTÍAS, E.; PÉREZ, E. 1993. Formulación de un modelo generalizado para la determinación de las curvas de desarrollo de calibres de aceitunas, Valle de Azapa, I Región (Chile). IDESIA. 12:71-78.

41. TAPIA, M.L.; LÓPEZ, X.I.; GALLETI, L.; BERGER, H. 1998. Caracterización del crecimiento y desarrollo del fruto de melón (Cucumis melo var. Reticulatus Naud.) cv. Topscore. Agri. Téc (Chile). 58(2):93-102.

42. TORRES, R.; MONTES, E.J.; PÉREZ, O.A.; ANDADE, R.D. 2013. Relación del color y del estado de madurez con las propiedades fisicoquímicas de frutas tropicales. Información Tecnológica 24(3):51-56.

43. UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA AGRICULTURE & NATURAL RESOURCES. Weather, models, & degreedays. Retrieved from www.ipm.ucdavis.edu/WEATHER/index.html (accessed on 06/04/2013).

44. VILLANUEVA, R.; EVANGELISTA, S.; ARENAS, M.L.; DÍAZ, J.C.; BAUTISTA, S. 1999. Evaluación de la calidad del jugo de maracuyá (Passiflora edulis) durante el crecimiento del fruto. Rev. Chapingo Serie Horticultura (México). 5(2):95-101.

45. VILLEGAS, J.R.; GONZÁLEZ, V.A.; CARRILLO, J.A.; LIVER, M.; SÁNCHEZ DEL C, F.; OSUNA, T. 2004. Modelos empíricos del crecimiento y rendimiento de tomate podado a tres racimos. Fitotec. Mexicana.27(1):63-67.

Received: 10 January 2014 Accepted: 11 September 2014

Revista U.D.C.A Actualidad & Divulgación Científica por Universidad de Ciencias Aplicadas y Ambientales se distribuye bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial 4.0 Internacional.