CIENCIAS EXACTAS Y NATURALES-Artículo Científico

DENSITY OF DOMESTIC PIGEONS (Columba livia domestica GMELIN, 1789) IN THE NEW PUBLIC MARKET OF SINCELEJO, SUCRE, COLOMBIA

DENSIDAD DE PALOMA DOMÉSTICA (Columbia livia domestica GMELIN, 1789) EN EL NUEVO MERCADO PÚBLICO DE SINCELEJO, SUCRE, COLOMBIA

Carmen Villalba-Sánchez1, Alejandro De La Ossa-Lacayo2Jaime De La Ossa V3

1Zootecnista, Maestría en Ciencias Ambientales. Universidad de Sucre - SUE, Caribe, Colombia, e-mail: carmenvillabasanchez@ gmail.com

2 Ecólogo, Magister, Grupo de Investigación en Biodiversidad Tropical. Universidad de Sucre, Colombia, e-mail: alejandrodelaossa@yahoo.com

3 Ph.D., Grupo de Investigación en Biodiversidad Tropical, Facultad de Ciencias Agropecuarias. Universidad de Sucre, Colombia, calle 13 A N° 20-45, Apto. 402. Edif. El Cairo. Barrio Ford. Sincelejo, Sucre, Colombia, e-mail: e-mail: jaimedelaossa@yahoo.com

Rev. U.D.C.A Act. & Div. Cient. 18(2): 497-502, Julio-Diciembre, 2015

SUMMARY

The present study determined the population density of Columba livia domestica in the new market of Sincelejo, Sucre, Colombia. It is known that, when populations of this species increase excessively, a serious public health problem is created that must be dealt with in order to avoid the transmission of zoonotic diseases. In the city of Sincelejo, especially in the study area, the magnitude of this species' population is unknown, as is the case in many cities in Colombia where this bird has become a serious environmental threat. For ten continuous days, between 06:00 and 08:00, fixed point sampling was used with timed counts; likewise, measurements were taken for the noise levels found in the study area. There were no statistical differences for the population detected in each sampling site for the ten sampling days or the study sites and hours. The estimated population was 257 individuals with a SD= 10.7; the estimated density was 574 ind/km2; the peak noise levels fluctuated between 68.2 and 83.5 decibels. The calculated density was lower when compared to other studies but higher than the density that has been established as harmful for this species in urban populations. During the sampling hours, the noise levels found in the population were high but tolerable. Population studies of this species in urban environments are necessary in order to implement management plans and programs that prevent the possible proliferation of zoonotic diseases.

Key words: Abundance, Columbiformes, urban environment, Sucre.

RESUMEN

El presente trabajo determinó la densidad poblacional de Columba livia domestica en el nuevo mercado de la ciudad de Sincelejo, Sucre, Colombia. Se conoce que cuando las poblaciones de esta especie se incrementan desmedidamente, se convierte en un serio problema de salud pública, que debe ser atendido, para evitar la transmisión de enfermedades zoonóticas. En Sincelejo, especialmente en la zona de estudio, se tenía desconocimiento de la magnitud de su población, al igual que sucede para muchas otras ciudades de Colombia, en donde esta ave es una seria amenaza ambiental. Durante diez días continuos, entre las 06:00 y las 08:00 horas, con conteos cronometrados, se aplicó el método de muestreos en punto fijo; igualmente, se hicieron medidas de los niveles de ruido existente en el área de trabajo. No se determinaron diferencias estadísticas para la población detectada en cada sitio de muestreo, ni durante los diez días de muestreo, ni entre los sitios de trabajo y los horarios. La población estimada fue 257 individuos, con una DS= 10,7, la densidad estimada fue de 574 ind/km2; los niveles sonoros máximos oscilaron entre 68,2 y 83,5 decibeles. La densidad calculada es menor al compararla con otros estudios, pero sobrepasa la densidad establecida como nociva, para esta especie, en poblaciones urbanas; durante el horario de muestreo, los niveles de ruido que soportó la población se establecen como altos y tolerables. Los estudios poblacionales de esta especie, en ambientes urbanos, se hacen necesarios para poder implementar planes o programas de manejo, que eviten posibles proliferaciones zoonóticas.

Palabras clave: Abundancia, columbiformes, ambiente urbano, Sucre.

INTRODUCTION

The domestic pigeon (Columba livia domestica) is a columbiform that has a average size between 30.5 and 35.5cm, with a medium-sized tail that has a blackish tip and a creamy-white base, reddish or pinkish paws, and amber eyes, and that are dark when juvenile. The color of the plumage can vary greatly between individuals and there is no sexual dimorphism between males and females. The base pattern is gray with two large, black bands on the wings, a black band at the tip of the tail, a white rump and purple and green iridescence on the neck. However, the majority of individuals have other colors, from white or whitish with irregular red or black markings on the primary feathers and a white tail. The weight oscillates between 180 and 355g (Del Hoyo et al. 1997; Gómez de Silva et al. 2005). It is a diurnal species found in natural habitats and nests in coastal cliffs or high inland areas. In urban environments, it tends to congregate in flocks that can number in the hundreds. Habitually, they move, fly, and perch together. They stay on roofs, ledges, drainage ducts, lofts, and attics, where they construct nests of dry branches and grass that are placed on a simple base. The male protects the female and the nest, ensuring the survival of the offspring (Johnston, 1992; Olalla et al. 2009).

Reproductively, it is known that, eight to twelve days after mating, the female lays one or two eggs that hatch eighteen days later. The offspring leave the nest at six weeks of age. These short reproductive periods, added to the ability to mate year-round, explain, in part, the abundance of this species' populations (Olalla et al. 2009).

According to Del Hoyo et al. (1997), this species originated from a wide area of Eurasia and Africa; specifically, its original distribution in Africa was: Cape Verde, Guinea, Mauritania, and Senegambia; in Asia: China: Gansu, Jilin and Shanxi; in Europe: Spain, the Canary islands, Great Britain, Portugal, the Madeira Islands, and the Azores Islands; in the Pacific: Australia and New Zealand (Gómez de Silva et al. 2005). This species, also known as the common pigeon or rock pigeon, is considered an introduced species that has been domesticated and raised in homes as an ornamental bird (Escalante et al. 1996; Ojasti, 2001; Méndez-Mancera et al. 2013).

Nevertheless, after being domesticated in captivity, they have returned to the wild, seeking refuge and food in diverse locations (Méndez-Mancera et al. 2013). According to the IUCN, this species is listed as of least concern; it has no special status under the US Migratory Bird Act, the US Federal List, or CITES. However, according to Mathews (2005), it is identified as one of the worst urban birds of the world due to its effects, which include structural damage and zoonotic risks.

Bernal et al. (2012) concluded that, among the bigger problems caused by pigeons, there is the corrosion caused by the accumulation of excrement, which affects the historical architecture of cities. In addition, this species can carry around 40 zoonotic diseases, with 30 diseases that can be transmitted to humans and 10 diseases that be transmitted to domestic animals, causing public health problems (Pfeiffer & Ellis, 1992; Ordóñez & Castañeda, 1994). Generally, these diseases are transmitted by the dry excrement, through transport by air or direct contact (Pfeiffer & Ellis, 1992; Ordóñez & Castañeda, 1994).

The domestic pigeon is a carrier for more than 60 ectoparasites, which include siphonaptera and mites, possibly contaminating and affecting human health with their feathers and dust. Some of the diseases that are related to pigeons include salmonellosis, psittacosis, cryptococcosis, aspergillosis, listeriosis, staphylococci and dermatosis, among others (Caicedo et al. 1996; Toro, 2000; Olalla et al. 2009).

Since they group together in large flocks, generally in zones of high human traffic such as plazas or markets, they affect motor and foot traffic. Their nesting in residential roofs produces bothersome noise that can even affect nighttime rest (CONABIO, 2012). In addition, this bird presents a medium risk for airports (Garmendia-Zapata et al. 2011).

According to Olalla et al. (2009), pigeons have fulfilled a role as messengers along with use in recreation, tourism, therapy and decoration, when the populations were controlled, that is to say: low number of individuals, ideal locations, and optimal health conditions. On the other hand, when they are found in large numbers in urban areas, they become a pest capable of transmitting disease, contaminating food and damaging structures, resulting in large economic losses. The common pigeon has created a serious urban problem, leading to it being called a "rat with wings." This species is considered a harmful vertebrate (CONABIO, 2012). Nevertheless, in Chile, they contribute to the dispersion of some thistle species, whose fruits they consume (Mann, 2008).

In Colombia, there are few studies related to this species (Méndez-Mancera et al. 2013) and the current population of most cities is unknown (Baptiste & Múnera, 2010). Villalba- Sánchez & De La Ossa-Lacayo (2014) confirmed that there still exists a lack of information for this species in anthropic environments, which must be remedied for epidemiological and ecological areas to deal with the negative consequences this bird can generate.

The present study determined the population density of C . livia domestica in the new market of Sincelejo, Sucre, Colombia, as a first step in creating subsequent guidelines for the environmental management that has become necessary due to the possible effects this bird can generate.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

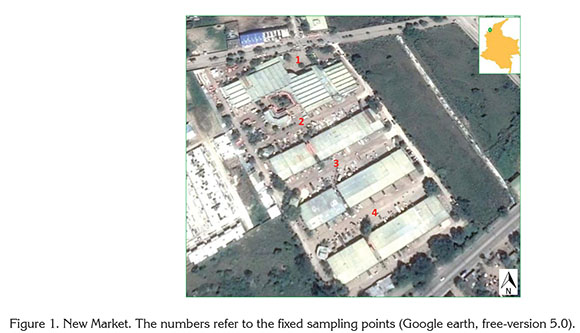

Study area. This study was carried out in the new public market in Sincelejo, Sucre, Colombia. This market constructed in 2000, is located at 9°17'41''N and 75°23'11''W in the south of the city, and has a total area of 44,800m2, with an open area of 14,000m2 represented by broad causeways (Figure 1). This area, like in all of Sincelejo, does not have an environmental plan in place for the control of domestic pigeon populations or for the sanitation of said populations.

Sampling. Total sampling was used (Feninger, 1983; Geupel et al. 1992; Gregory et al. 2004; Torres et al. 2006) for ten days in the dry season between the 1st and 10th of January, 2015 in four strategic sites with simultaneous sampling (Figure 1) using open areas where the birds usually look for food. One session was used per day, between 06:00 and 08:00, with three counts at 06:00, 07:00, and 08:00 and one observer per site at a distance of 15m. The study hours were chosen based on the fact that the majority of feeding activity occurs early in the morning (Olalla et al. 2009) and that the feeding rhythms are more robust than the locomotion rhythms (Chabot & Menaker, 1992).

According to Verner & Milne (1989), simultaneous and timed sampling in fixed points guarantees the absence of samples moving between the sampling sites, in addition it takes into account the gregarious nature of this species, which demonstrates a high degree of congregation and the permanence of individuals within the groups (Olalla et al. 2009). At the same time, during the ten days of the study, the noise levels were measured in the study area with two daily readings at 07:00 and 08:00 using a Svan 971 ® sound level meter.

Data analysis. The comparison of the density between the sampling sites, study days and hours was carried out with an ANOVA of the repeated measurements and a Kruskal-Wallis test with a significance level of 0.05. Likewise, the gross density was estimated (Krebs, 1989; Zar, 1998; Marques et al. 2007), for which the total population was established with the sum of the means of each sampling site multiplied by the total number of sampling sites, for an area of 44,800m2.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

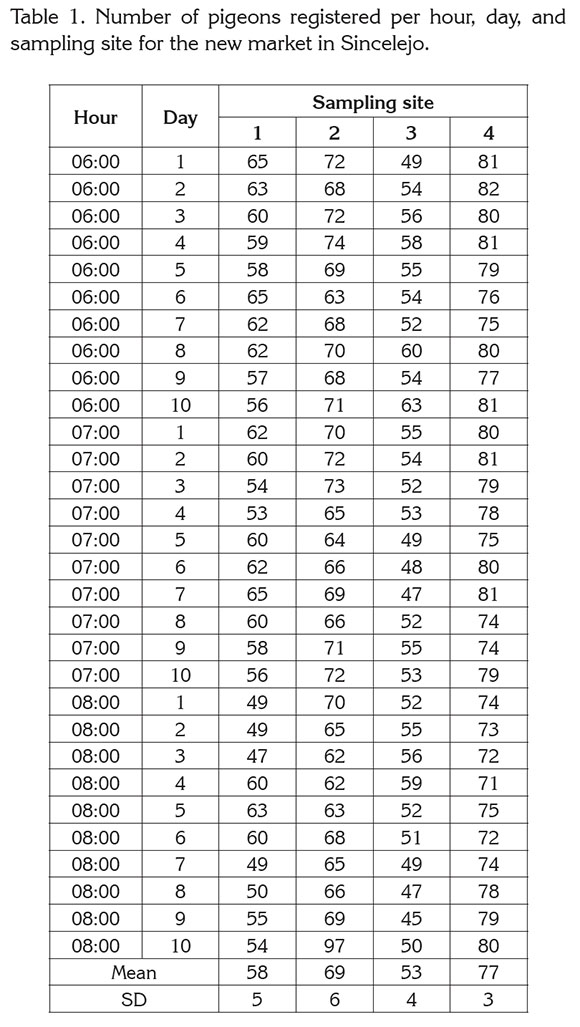

The number of individuals registered per hour and per sampling site can be seen in table 1. When applying the ANOVA for the repeated measurements, there were no statistically significant differences for the number of individuals in the four sampling sites F(36, 42.092)=1.3411, p=0.17916; there were also no significant variations in the number of individuals for the sampling sites during the study when the Kruskal-Wallis test was applied: (H ( 10, N= 11) =10.00, p=0.4405). When comparing the study hours with the population detected in each of the four sampling sites, no statistical differences were determined with the Kruskal - Wallis test: (H (2, N= 3) =2.00, p=0.3679.

According to the registered means, there was a population of 257 individuals (SD=10.7). The estimated total density was 57.36ind/ha. The density seen in this study was lower than the range of 75 to 225ind/ha determined for the city of Buenos Aires, Argentina (Feninger, 1983), but higher than the values reported by Senar & Sol (1991) for Barcelona, Spain, where 9.78ind/ha were seen with a non-stratified census along with a range of 8.14 to 28.49ind/ha with stratified sampling, without a correlation factor and with a correlation factor, respectively. Nevertheless, a density over 4ind/ha is considered harmful and presents a serious environmental problem; however, this number can vary according to the environmental characteristics of the location (Botanical on line, 2014).

In nature, the values vary notably. In Spain, the Proyecto Alas (Wings Project) by Nerpio (2013) estimated a density of 0.006ind/ha, which agreed with Olalla et al. (2009) and Bernal et al. (2012), who regarded this species as invasive, one that had successfully established itself in urban environments due to the fact that it had encountered suitable shelter and available food sources in these areas. Furthermore, according to Johnston (1992) and Olalla et al. (2009), the relative absence of predators has allowed large-scale increases in populations, as seen in the present research and in similar studies in urban zones (Feninger, 1983; Senar & Sol, 1991). The environmental conditions of a location influence the population abundance (Olalla et al. 2009; Bernal et al. 2012); the new market in Sincelejo offers food that enables a comparatively elevated density as seen in this study, which also occurs in other locations in this city, as well as in other cities in Colombia and the world (Gómez de Silva et al. 2005; Mann, 2008; Bernal et al. 2012).

The noise levels mainly result from automobiles. In the sampling hours and in the four study sites, the noise levels were similar and oscillated between 68.2 and 83.5 decibels. The noise level found in the present study area does not disturb the activity of the pigeons despite the high level. Feninger (1983) reported that the noise from motorized vehicles in a study area reached values between 80 and 110 decibels without provoking visible reactions in the mentioned species, which agrees with the results of the present study.

Taking into account the fact that C . livia domestica is regarded as a pest species that generates various negative effects, especially on human health (Pfeiffer & Ellis, 1992; Ordóñez & Castañeda, 1994; Bernal et al. 2012), recording its density, especially in areas such as public markets, is a priority for environmental management, which has become necessary for urban populations (Semarnat, 2009).

Without a doubt, the high population density that was recorded in the present study for the public market, a place that mostly contains foods, led to the conclusion that this population could have a large, negative impact on sanitation, especially since there are no control plans or population management strategies in place.

This study led to the recommendations that, in general, population control measures that are based on eliminating individuals are not very effective, rather, as indicated by Senar et al. (2009), it is better to focus on control methods based on the limiting factors of this species, that is, the availability of food and nesting areas. In order to make elimination an effective method, at least 30% of the population must be sacrificed (Senar et al. 2009).

For example, in Perugia, Italy, the pigeon population was reduced by 23% in one year by simply closing the ventilation openings in buildings with metal sheeting, thereby reducing the availability of nesting areas (Ragni et al. 1996). In Basel, Switzerland, controlling the amount of food offered by citizens reduced the pigeon population by 50% in one year (Haag- Wackernagel, 1995). In both cases, low-cost measures were taken that were effective and that could be applied to the new public market of Sincelejo.

Conflicts of interest: This manuscript was prepared and revised with the participation of all of the authors, who declare that there are no conflicts of interest that would affect the validity of the present results.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. BAPTISTE, M.P.; MÚNERA, C. 2010. Análisis de riesgo para especies introducidas de vertebrados terrestres en Colombia (anfibios, reptiles, aves y mamíferos). En: Baptiste M.P.; Castaño, N.; Cárdenas, D.; Gutiérrez, F.P.; Gil, D.L.; Lasso, C.A. (eds). Análisis de riesgo y propuesta de categorización de especies introducidas para Colombia. Instituto de Investigación de Recursos Biológicos Alexander von Humboldt (Bogotá, Colombia). p.149-199.

2. BERNAL, L.; RIVAS, M.; RODRÍGUEZ, C.; VÁSQUEZ, C.; VÉLEZ, M.P. 2012. Nivel de impacto de la sobrepoblación de palomas (Columba livia domestica) en los habitantes del perímetro del parque Principal del Municipio de Envigado en el año 2011. Available from internet in: http://marthanellymesag.weebly.com/uploads/6/5/6/5/6565796/palomas.pdf(accessed 28/08/2014).

3. BOTANICAL ON LINE. 2014. La paloma como plaga. Available from Internet in: http://www.botanical-online.com/animales/paloma_plaga.htm (accessed 20/11/2014).

4. CAICEDO, L.D.; ÁLVAREZ V., M.I.; LLANOS, C.E.; MOLINA, D. 1996. Cryptococcus neoformans en excretas de palomas del perímetro urbano de Cali. Colombia Médica (Colombia). 27:106-109.

5. CHABOT, C.C.; MENAKER, M. 1992. Circadian feeding and locomotor rhythms in pigeons and house sparrows. J. Biol. Rhythms. (USA). 7(4):287-99.

6. COMISIÓN NACIONAL PARA EL CONOCIMIENTO Y USO DE LA BIODIVERSIDAD -CONABIO-. 2012. Fichas de especie Columba livia . Sistema de información sobre especies invasoras en México. Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad, México, D.F. (México). 15p.

7. DEL HOYO, J.; ELLIOT, A.; SARGATAL, J. 1997 .Handbook of the birds of the world. Vol. 4. Sandgrouse to Cuckoos. Lynx Ediciones, Barcelona. (España). 679p.

8. ESCALANTE P., B.P.; SADA, A.M.; ROBLES G., J. 1996. Listado de nombres comunes de las aves de México. CONABIO/Sierra Madre. México, D.F. (México). 32p.

9. FENINGER, O. 1983. Estudios cuantitativos sobre aves en áreas urbanas de Buenos Aires con densa población humana. El Hornero (Argentina). 12(1):174-191.

10. GARMENDIA-ZAPATA, M.; LÓPEZ, A.A.; MUÑOZ IZAGUIRRE, P.; MARTÍNEZ GADEA, A. 2011. Estudio sobre peligro aviario: análisis del riesgo de impactos entre aves y aeronaves en el Aeropuerto Internacional Augusto C. Sandino, Managua, Nicaragua. La Calera (Nicaragua). 11(16):33-42.

11. GEUPEL, G.R.; HOWELL, S.N.G.; PYLE, P.; WEBB, S. 1992. Ornitología de Campo Tropical, curso de identificación de aves neotropicales y métodos de monitoreo de sus poblaciones. Centro de Aves Migradoras de la Smithsonian Institution, U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Point Reyes Bird Observatory, Stinson Beach, California. (USA). 45p.

12. GÓMEZ DE SILVA, H.; OLIVERAS DE ITA, A.; MEDELLÍN, R.A. 2005. Columba livia . Vertebrados superiores exóticos en México: diversidad, distribución y efectos potenciales. Instituto de Ecología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Bases de datos SNIB-CONABIO. Proyecto U020. México. D.F. (México). 6p.

13. GREGORY, R.D.; GIBBONS, D.W.; DONALD, P.F. 2004. Bird census and survey techniques. En: Sutherland, W.J.; Newton, I.; Green, R.E. (eds): Bird Ecology and Conservation - A Handbook of Techniques. Oxford University Press Inc. New York. (USA). p.17-52.

14. HAAG-WACKERNAGEL, D. 1995. Regulation of the street pigeon in Basel. Wildl. Soc. Bull. (USA). 23:256-260.

15. JOHNSTON, R.F. 1992. Rock Pigeon (Columba livia). En: Poole, A. (ed.). The Birds of North America. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca. Available from Internet in: http://bna.birds.cornell.edu/bna/species/013 (accessed 10/06/2014).

16. KREBS, C.J. 1989. Ecological methodology. Harper Collins, New York. (USA). 653p.

17. MANN, A. 2008. Vertebrados dañinos en Chile: desafíos y perspectivas. Actas del Seminario Taller 8. Enero de 2008. Universidad Santo Tomás, Santiago de Chile. Available from Internet in: tarhttp://www2.sag.gob.cl/Pecuaria/bvo/BVO_11_I_semestre_2010/PDF_articulos/vertebrados_exoticos_daninos_en_ chile.pdf (accessed 23/06/2014).

18. MARQUES, T.A.; THOMAS, L.; FANCY, S.G.; BUCKLAND, S.T. 2007. Improving estimates of bird density using multiple covariate distance sampling. Auk (USA). 124:1229-1243.

19. MATHEWS, S. 2005. Sudamérica Invadida. Programa Mundial sobre Especies Invasoras- GISP. El creciente peligro de las especies exóticas invasoras. Unesco. (Uruguay) 80p.

20. MÉNDEZ-MANCERA, V.M.; VILLAMIL JIMÉNEZ, L.C.; BUITRAGO MEDINA, D.A.; SOLER-TOVAR, D. 2013. La paloma (Columba livia) en la transmisión de enfermedades de importancia en salud pública. Rev. Cien. Anim. (Colombia). 6:177-194.

21. OJASTI, J. 2001 . Estrategia Regional de Biodiversidad para los países del Trópico Andino. Especies exóticas invasoras. Convenio de cooperación CAN-BID, Caracas. (Venezuela). 64p.

22. OLALLA, A.; RUIZ, V.; RUVALCABA, I.; MENDOZA, R. 2009. Palomas, especies invasoras. CONABIO. Biodiversitas (México). 82:7-10.

23. ORDÓÑEZ, N.; CASTAÑEDA, E. 1994. Serotipificación de aislamientos clínicos y del medio ambiente de Cryptococcus neoformans en Colombia. Biomédica (Colombia). 14:131-139.

24. PROYECTO ALAS PARA NERPIO. 2013. II Censo Coordinado de aves en los Noguerales de Nerpio. Available from Internet in: www.turismonerpio.com/.../in forme-censo-aves-de-los-noguerales-2013 (accessed 10/10/2014).

25. PFEIFFER, T.J.; ELLIS, D.H. 1992. Environmental isolation of Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii from Eucaliptus tereticornis. J. Med. Vet. Mycol. (UK). 30:407-408.

26. RAGNI, B.; VELATTA, F.; MONTEFAMEGLIO, M. 1996. Restrizione dell'habitat per il controllo della popolazione urbana di Columba livia . En: Control of Synanthropic bird populations: problems and prospectives: WHO/FAO. Roma. (Italia). p.106-110.

27. SECRETARÍA DE MEDIO AMBIENTE Y RECURSOS NATURALES -SEMARNAT- . 2009. Plan de Manejo Tipo de Palomas Dirección General de Vida Silvestre, México. Available from Internet in: www.semarnat.gob.mx (accessed 10/10/2014).

28. SENAR, J.C.; SOL, D. 1991. Censo de Palomas Columbia livia var. de la ciudad de Barcelona: Aplicación del muestreo estratificado con factor de corrección. Bull. GCA (USA). 8:19-24.

29. SENAR, J.C.; CARRILLO, V.; ARROYO, L.; MONTALVO, T.; PERACHO, V. 2009. Estima de la abundancia de palomas (Columba livia var.) de la ciudad de Barcelona y valoración de la efectividad del control por eliminación de individuos. Arxius de Miscellània Zoològica (España). 7:62-71.

30. TORO, H. 2000. Palomas: Historia, presencia en Chile y riesgos asociados. Tecno Vet. (Chile). 6:20-23.

31. TORRES, M.; QUINTEROS, Z.; TAKANO, F. 2006. Variación temporal de la abundancia y diversidad de aves limícolas en el refugio de vida silvestre Pantanos de Villa, Perú. Ecol. Apl. (Perú). 5(1-2):119-125.

32. VERNER, J.; MILNE, K.A. 1989. Coping with sources of variability when monitoring population trends. Ann. Zool. Fennici (Finlandia). 26:191-200.

33. VILLALBA-SÁNCHEZ, C.; DE LA OSSA-LACAYO, A. 2014. Columba livia domestica Gmelin, 1789: plaga o símbolo. Rev. Col. Cienc. Anim. 6(2):424-433.

34. ZAR, J.H. 1998. Biostatistical analysis. Prentice Hall. (USA). 662p.

Received: 17 April 2015 Accepted: 3 July 2015

Revista U.D.C.A Actualidad & Divulgación Científica por Universidad de Ciencias Aplicadas y Ambientales se distribuye bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial 4.0 Internacional.